Two defendants accused of organizing illegal border crossing were sentenced to two and three years’ imprisonment, respectively. The other eight were convicted of participating in the border crossing and were all sentenced to seven months in prison. The Yantian People’s Court said the ten pleaded guilty. All defendants received fines ranging from $ 1,500 to $ 3,000.

Earlier Wednesday, China handed over two suspects under the age of 18 who were on the boat to Hong Kong police. Authorities in the southern city of Shenzhen said they had confessed to crossing the border illegally but had not been charged.

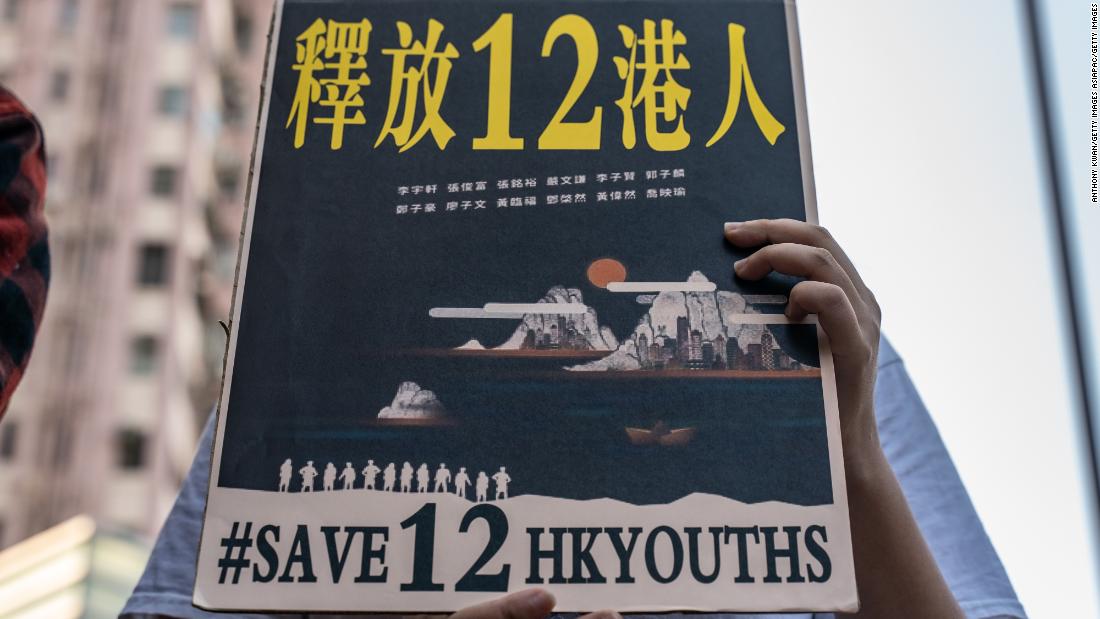

All 12 people were held for more than 100 days before this week’s trial in Shenzhen, as their parents and politicians in Hong Kong, the United States and the United Kingdom pressed for their release. A group representing the families of the defendants said that their loved ones were ill-treated in Chinese custody and denied access to their lawyers.

Police and prosecutors in Shenzhen previously denied accusations of ill-treatment and claimed that the 12 had access to legal advice, although the practice in mainland China of denying defendants their attorneys by appointing a government-chosen attorney has been well documented in the past.

On Monday, a US State Department spokeswoman urged Beijing to release the 12 and allow them to leave the country, adding that their alleged “crimes” are fleeing tyranny.

“The treatment by the People’s Republic of China authorities of these 12 individuals, some of them minors, was appalling,” the spokeswoman said. “The Beijing authorities continue their campaign to eliminate the remaining rights and freedoms of Hong Kong people, and falsely equate their system of government by party decree with the rule of law.”

The fate of the 12 activists has attracted great attention both in Hong Kong and beyond, symbolizing the deterioration of political freedoms and the climate in the city since the passage of a new national security law earlier this year. The law – which Beijing has imposed on the city, bypassing Hong Kong’s quasi-democratic legislature – criminalizes secession, sabotage, and collusion with foreign forces, and has already had a chilling effect on politics and debate.

Chung reportedly tried to flee the city in October by seeking asylum at the US consulate, but was turned away.

The ways to escape have grown continuously this year, exacerbated by closures and closures around the world as a result of the Coronavirus pandemic. The once viable, albeit risky, sea route to Taiwan was closed once the Chinese Coast Guard explained that they were monitoring the waters around the city.

Carrie Lam, the Beijing-appointed chief executive of the city, has refuted any indication that the Hong Kong government had known about or was involved in the case prior to the arrest of the 12.

She said in October that the fugitives “chose to flee, and as they fled they entered another jurisdiction and committed the crime of entering another place illegally.” “They have to face the legal consequences in that jurisdiction. It’s that simple and clear.”

The prospect of facing trial in China has been a major source of opposition to the proposed extradition bill that sparked protests last year, and the fate of the 12 appears to demonstrate many of the concerns that Hong Kong has felt. The activists were allegedly denied access to adequate legal representation, and little information was provided on their condition.

Chinese courts – along with prosecutors and police – are overseen by the powerful Central Political and Legal Affairs Committee of the Communist Party of China and its local branches.

In a statement, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for Asia and the Pacific, Yamini Mishra, said the sentences “issued after an unfair trial reveal the dangers faced by anyone who finds himself being tried under the Chinese criminal system”.

“The Chinese authorities have shown the world once again that political activists will not get a fair trial,” she added.

“Appassionato pioniere della birra. Alcolico inguaribile. Geek del bacon. Drogato generale del web”.